I’m planning to cross the Pacific on a cargo ship from New Zealand to California. However, that plan nearly fell apart when one German word blocked my entry to New Zealand.

Eigner: from an agent derivative of Middle High German aigen ‘own’, a status name originally denoting a smallholder who held his land outright, rather than by rent or feudal obligation.

Source: www.ancestry.com

As some of you may know already, I’m planning to cross the Pacific Ocean as a passenger on a cargo ship. The cargo vessel was originally estimated to leave on Saturday 8th of July. The whole journey from Tauranga, New Zealand, to Oakland, California, should take approximately 18 days.

While planning my cargo ship voyage, there was one risk that I didn’t take into account: the fact that I might be stopped from entering to New Zealand. Yet this was exactly what happened.

I have to warn you: this blog post has very lame photos. Like this out-of-place picture from Tonga.

The Annoyance of Crossing Borders

The more I travel, the more I dislike visas and border crossings. No, I’m not generally against border control – of course all countries have some right to supervise the movement of people. I just find the arrival procedures ill-suited for backpackers.

For example, most arrival cards ask for my permanent address (which I don’t really have) and the address where I stay in the country (which I may or may not have). Having a local host often leads to further questioning, and I still haven’t met an immigration officer who’d understand how CouchSurfing works.

The rule I dislike the most, though? That’s the requirement of having a return/onward ticket. You can’t just plan your trip as you go – you need to book a ticket out of the country even before you arrive. Even if you’d plan to cross a border on a bus, boat or bicycle, these kind of excuses for missing tickets are rarely accepted.

Many backpackers craft fake return tickets or book refundable flights just to get into countries. I haven’t done this myself, but the popularity of these solutions shows how rigid the border bureaucracy can be. If you want to cross borders smoothly, lying your way in is the easiest solution.

This onward ticket rule started my troubles on my way to New Zealand. Had I been less honest, I would have probably boarded my flight quite easily. But where’s the fun in that?

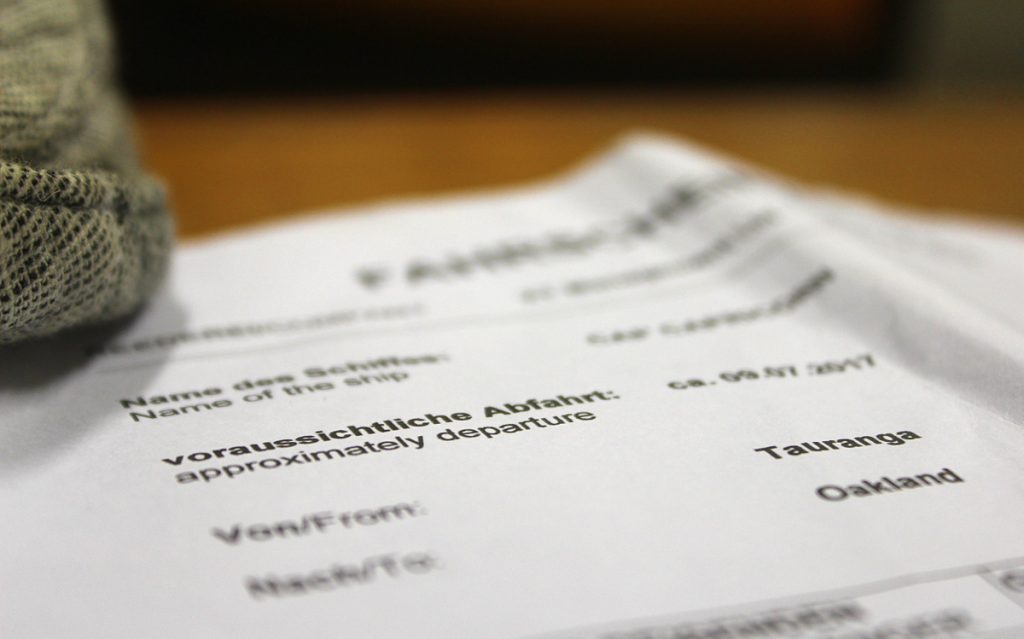

My cargo ship passenger ticket is written in both German and English. Only one German word is not translated.

How Harmful Can One German Word Be?

The Finnish passport is very strong for traveling, so I rarely have to go through the visa hassles that most people of the world face. To enter New Zealand, I wouldn’t even need to apply for a visa in advance. As long as I had a return ticket, I’d be allowed to enter.

I knew about this rule, and I had prepared myself. I had asked my travel agent Hamish to send me a ticket for the cargo ship. Hamish, who organized the communication between me and the cargo ship company, delivered the ticket on email a day before my flight from Tonga to Auckland, New Zealand.

Now, what does a passenger ticket for a cargo ship look like? The ticket might look deceivingly simple: there’s no booking reference, exact departure time or bar code that might be found on a flight ticket. Still, my ticket had all the necessary information.

There was only one slightly confusing feature in the ticket. As the cargo ship company was German, all the texts were written in both German and English. All except one word. The name of my cabin had not been translated, so the part about my cabin number only said “Eigner 801”.

Eigner is a German word for owner. My cabin called owner’s cabin, because it’s larger than the other passenger cabins on board. I didn’t really want a bigger cabin, but it just happened to be the last one available.

However, the meaning of the word doesn’t really matter in this story. What’s important is what English word “eigner” might sound like. You know, like some technical profession, perhaps?

Another super exciting picture from the Nuku’alofa airport check-in! No, I don’t expect to win any photography awards with these shots.

Check-In for Trouble

I had booked my flight from Tonga to New Zealand for Friday June 30th. So, when Friday came, I checked out of my hostel and took a taxi to the airport. I arrived in the airport approximately 90 minutes before the flight’s departure. All was well.

There wasn’t a lot of queue at the airport, and I made it to the check-in counter very quickly. I routinely lifted my backpack on the conveyor belt and gave the check-in worker my passport. She printed my flight ticket and asked for my return ticket. I had my cargo ship ticket ready on my phone. I handed it to her.

I could see that the worker hadn’t seen a passenger ticket for a cargo ship before. I explained her what it was. She asked me to wait and went to the back room to ask for guidance.

She soon returned without my phone and asked me further details about my onward journey. What was the name of the ship? I repeated the name several times until she was able to write it down somewhat correct. Was I the owner of this ship? No, I’m a passenger, I repeated, having told the same things just a few minutes earlier.

The check-in worker told me to wait again and left to the back room for a second time. After a while, I was asked to come with her. I’d need to talk with the New Zealand immigration, I was told.

Becoming “Engineer 801”

There was a narrow corridor behind the check-in counters. I was led to last door on the corridor, a small office with a phone on the table. When I answered the phone, I was greeted by a worker of New Zealand immigration who remained anonymous. She wanted to know more about my cargo ship trip, asking me about the route and details of my journey.

The check-in worker had not really understood what I had explained to her about the trip, so I had to explain things again for the immigration officer on the phone. No, I was not returning to Tonga, I was going to California. No, I’m not leaving from Auckland, but I’m heading to Oakland (“O-A-K land”, I spelled it out). This went on for quite a while.

Then she said something that took me by surprise. I didn’t really hear what source she said she had, but the immigration officer told me I was working as “Engineer 801” on the cargo ship. If I was just a passenger, how could I explain that?

Okay, I ran out of airport photos. Here’s a picture from a Nuku’alofa bus station.

Okay, I know I should have asked where she got the information from. Or even better, I should have instantly understood the connection between “Engineer 801” and my cabin’s name, “Eigner 801”. But I have my excuses: The situation was very weird, I had trouble hearing her, I didn’t feel like I was in a position to question an authority…

Or, my favourite explanation: I’m very good at being stupid at times.

At that moment, I just assumed she had contacted the cargo ship company or someone else to get the information. I thought she really knew. I was only able to say that perhaps I was given some job title for bureaucracy reasons. After all, I’ve heard that’s really done at times. Still, I assured that I was only a passenger on the ship. The whole case of my engineering was never mentioned again.

After that, the discussion was stuck on a cycle for a long time. She asked me several times to repeat what my ticket said. I read it aloud – I even mentioned my cabin name “Eigner 801”, but neither one of us really reacted to it. She asked me what I would be doing on the ship for 18 days. Reading books and playing video games, I answered truthfully.

And so on. She put me on hold several times as she discussed my case with a colleague.

Eventually the verdict came. The immigration officer reminded me that it was illegal and punishable to lie to immigration officials. She believed I was going to work on the cargo ship. Therefore, I wouldn’t be allowed to enter New Zealand without a working visa.

Air New Zealand office in Nuku’alofa, the capital of Tonga.

Game Over. Try Again?

On my way out of the airport, I sent an email to my travel agent Hamish, telling him what had happened. Only at this point did I fully realize how the Tongan worker must have mistaken the one German word “eigner” for engineer, but it was too late to go back.

“This is madness”, Hamish wrote in his response. Even though I’ve never met my travel agent, I really, really like him. Hamish told me I should try to sort the mess out in the Air New Zealand office in Nuku’alofa.

Unfortunately, I didn’t have any more luck in the office. They told me that since the New Zealand immigration had not accepted my onward ticket, they wouldn’t revert their decision. Instead, I should book a refundable ticket out of New Zealand that I could cancel afterwards.

“So, should I book you to Australia, say, one month from now?” an Air New Zealand worker suggested innocently.

“Would Fiji be okay?” I responded, thinking about the easie, visa-free travel policies of the country.

Besides getting a slightly imaginary flight out of New Zealand, we also re-booked my flight from Tonga to Auckland. The clerk suggested a flight for the following day, and I agreed without much consideration. The flight I got would leave 10 pm and arrive in Auckland after midnight, which wasn’t the most convenient option. Still, it was better than nothing.

Preparing for Round Two

Meanwhile, my travel agent Hamish was calling the New Zealand Ministry of Immigration to “make a BIG complaint” as he told me. (Did I already tell you how much I like this guy?) I stopped for a lunch of noodle soup – this was also the moment when I told about my situation on my blog’s social media channels.

After lunch, I returned to my hostel and reconsidered my situation. I wasn’t sure if I wanted to show the onward flight ticket as Air New Zealand had suggested. If the New Zealand immigration had any records stating that I just tried to enter the country with a cargo ship ticket, there would be no chance they’d believe I’d fly out of the country. I thought I might be blocked out of New Zealand for good.

Besides, I don’t like to lie. And as I was considering my options, I remembered an article my friend Anu had shared on Facebook many years ago. I don’t remember much about that article, but it somehow dealt with living a good life. I only remember one point: “Live your life in a way that leads to the best story”.

Nah, forget the onward ticket, I thought. I’ll keep on trying to get in the honest way.

While waiting for my new flight, I had a chance to see a rugby match between Tonga and Samoa. Tonga won and the whole country went crazy.

Another Day, Another Flight Attempt

I went back to the airport the following evening. Hamish had written me a letter of certification, declaring that I was traveling on the cargo ship AS A PASSENGER (emphasis not mine). I had printed both my ticket and the letter of declaration.

The Ministry of Immigration had told Hamish that I should apply for a visitor visa – a process that may take 6-8 weeks. Too bad I only had a week before my cargo ship’s departure. The Ministry of Immigration was closed for the weekend, and Hamish couldn’t help me any further now. I began to regret booking my flight for Saturday.

Feeling anxious, I got into the airport three hours before the flight’s departure. There was no line at the check-in. I handed my passport at the desk and tried to stay calm, simply focusing on counting my breath.

One… two… three…

I realized that my heart was beating faster than usual, but I simply kept counting and waiting as the worker scanned my passport.

Four… five… six…

Fun fact: You know you’re in trouble when a worker at the check-in counter starts avoiding eye contact with you. She didn’t say anything yet, but I knew there were some issues with my passport. She asked her colleagues to help, and they all tried to log my passport details in the system.

Eventually they told me what was going on: “It says your passport is not allowed entry in New Zealand. Have you tried entering New Zealand before?”

I’ll just use this picture from the check-in twice and hope that nobody notices.

Back to the Back Room

I told the airport workers about the events of the previous day. Acting with newfound confidence, I said I hadn’t been allowed to board the plane despite a proper onward ticket as a passenger on a cargo ship. I insisted that there had been a mistake, adding that I now had a letter of declaration to prove I was just a passenger on the cargo ship.

Once again, the workers went to the back room and told me to wait. Once again, I was soon told to follow. After a while I was back on the same office as yesterday, once again talking with New Zealand immigration on the phone.

The immigration officer was not the same as the one yesterday. I told her what I think had happened. I explained how the Tongan worker must have mistaken the one German word “eigner” for engineer, and how that mistake had made her believe I was going to work on the ship. I told her how my new letter of declaration proved that I was just a passenger.

The silence after my long explanation felt amusing. She soon put me on hold.

It probably wouldn’t be okay to share too many pictures from the back room. Here’s an elusive photo of the office floor.

After she returned to the line, I felt like we were finally making progress. Or at least she asked me completely new questions, like how much money I had on me and where was I going to stay in New Zealand. I had to tell her about CouchSurfing, but luckily she believed me when I told her about it.

(CouchSurfing has nearly stopped from entering both India and Bangladesh, so I prefer to avoid mentioning it to immigration officials.)

In the end, she asked me to get the ticket manager on the phone. I had no idea who she meant, but after some initial confusion I forwarded her request to the single airport worker who was still in the room with me. He went out and soon returned with a bald, middle-aged white man.

The ticket manager went to the phone and read aloud what my passenger ticket and letter of declaration stated. I couldn’t hear what was said at the other end of the conversation, but they talked a little about the details of my ticket, referring to something that was written about my case on the files of New Zealand immigration.

Then: victory. The ticket manager was still talking on the phone, but I heard him repeat the instructions he got: “So it’s all good for check-in… and I can use your name for clearance?” I felt like hugging the man, but that might have been a bit too much.

Boarding our flight to Auckland, New Zealand

What’s Next?

I made it to New Zealand that night. By the time I arrived in my hostel in Auckland, it was well past 2 am. I was sick with flu and tired, but at least I was finally in the right country.

I’m currently waiting for the departure of my cargo ship in Tauranga. Other preparations are going well, although the unnecessary onward ticket I booked from Air New Zealand keeps causing me trouble. It wouldn’t have helped me enter New Zealand, and now canceling the flight has been much more difficult than I expected.

Instead of being able to cancel it in New Zealand like I was told, only the office in Tonga can cancel it. I contacted them via Facebook (their main email address didn’t work), and I had to send them a proof of another onward ticket just to cancel the one they had booked for me. I hope they’ll believe my cargo ship ticket is real, and I hope to finish the cancellation process before my ship departs.

The departure of my ship has been delayed till Monday 10th of July, but unless something very weird happens, I should be able to get on board.

Now I just need to hope that spending eighteen days on a cargo ship was a good idea.

Port of Tauranga, New Zealand

8 comments

This is such a mad story. Glad you got into NZ in the end mate, and I hope your cargo ship trip works out with a few less complications.

Given you a follow – I’m writing a travel blog too, perhaps take a look? Best of luck!

Thank you! 🙂 Luckily the cargo ship trip went much more smoothly.

I checked your blog, the Roman tunnels in Split seem interesting. Enjoy your trip to Japan!

OMG what an ordeal!

I guess not as bad as the film Argo, but still.

Meanwhile, your blog is so awesome!!! 🙂

Thank you Glenn! 🙂

Yeah, not as many hostages as in Argo, but otherwise quite close.

Really enjoyed reading this. When I went on my around-the-world-journey, I had really pushed the limits of ‘honest’ in so many areas, but somehow never got caught or tripped up once. Just lucky. Immigration people have not changed in 50 years.

Keep posting.

That’s interesting, thank you for sharing your experience Glen 🙂

This is madness! Thanks so much for sharing your experience, Arimo! We are in Australia right now, and we were thinking in sailing to the Americas… and… probably we won’t :·D

Thank you Roc, and good luck on your travels! 🙂 I’ve been following your journey on Instagram and Facebook, and it seems great!